Adaptive Façade

By Khaled Abou Alfa • 9th of October, 2020

As a building services engineer, one of the most difficult things I have found is explaining to people what it is that I do, while trying to instill poetry. Over the years I have developed an analogy that has served me well:

Think of a building not as a cold and lifeless form, rather think of it as a human body. Our skeletons act as the structure of the building. The nervous system is the electrical distribution. Our brain is the building management system. Our veins are the pipe work. Our lungs act like the ventilation system.

Across the built environment, we are creating living, breathing and indeed polluting entities. They may not be human but seen through a certain lens, they certainly try to resemble one. By this analogy, our skin would act as the façade. Our skin forms the final barrier and defence to the world around us. It has the ability to heal. Be porous when it needs to. It rejects toxins. It helps regulate our temperature. Stretches and contracts. It changes colour as a direct reaction to its environment. It has an amazing ability to adapt to the world around it.

In a similar way, building façades will provide the necessary protection from the outside work. Provide relief from the heat outside. Keep the warmth inside. Allow light to enter. For all it’s versatility, as long as it is behaving, the façade of a building will hang there for decades or centuries doing very little else. Replicating the adaptive nature of skin in the built world has proven much more difficult in practice. There are some notable examples including the Al Bahr towers in Abu Dhabi, the Milwaukee Museum of Art or the One Ocean in Yeosu-si, South Korea. These solutions are however bespoke and in many ways the defining feature of these buildings. They are outliers.

Adaptive façades remain a nascent field within the built environment, still operating on the fringes. This however is exactly what makes this field exciting to watch and observe. The two most active areas of development are concerned with two properties, visibility and movement.

Of the plethora of both baked and half-baked solutions, the following hold the most promise:

- Switchable glazing

- Movable solar shading

- Wall-integrated phase change materials

- Dynamic insulation

- Thin Glass

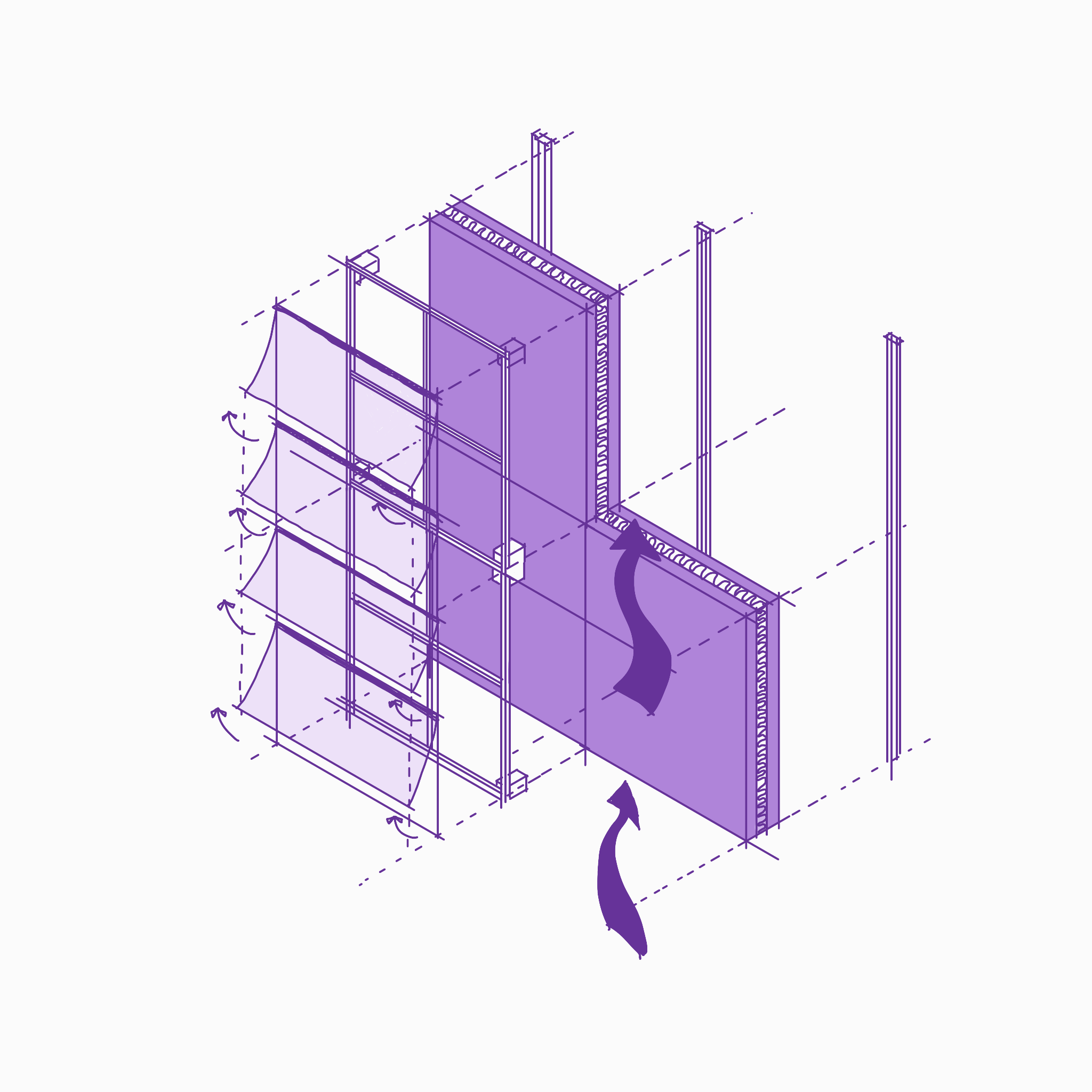

The last solution bears further consideration. While we covered architectural glass in issue 029, we did not dive into is thin glass. Thin glass is defined as glass with a thickness between 5-20mm. The magic of this particular glass is its incredible ability to bend and curve in a manner previously unimaginable. This innovation opens up a new avenue to be explored. No longer constrained by hinged systems, façades can bend, twist or curve. This movement can then controlled through the addition of secondary framing (bi-wood or bi-metal materials) or multiplier systems (a small movement in one area creates a much larger movement elsewhere).

A shift in the way we think about what is possible between the outside and inside worlds will need to occur as these technologies mature. The exact application of these techniques and materials will ultimately depend upon both perception and appetite. For these types of façades to proliferated, answering this precisely will move the question from why, to why not.

Commentary

David Attenborough: A Life on Our Planet

David Attenborough has amassed an incredible platform that he is using at the tender age of 94 to spread a message. A simple message really, framed using his own life as the thread that ties the narrative together. It is nothing less than one of the most important films that Attenborough has likely done in an oeuvre that spans decades. The most powerful moments are half way through the documentary and right at the end.

Bonus. As if that wasn’t enough, he has also contributed his silky voice to this Ellen MacArthur Foundation advert.

Ørsted Valuation

The only industry that has taken a more comprehensive beating than the airline industry, in 2020, has been the petroleum industry. In April the cost of petrol became negative for the first time in history.

Like the tortoise overtaking the hare, Ørsted (previously a footnote when compared with other energy providers) has surpassed Eni, Equinor and now BP in market capital. Shell and Total are out of its reach for this year but the smart money is that they are within the target zone for 2021.

Publications of Note

99% Invisible City

As a reader of this newsletter there is a larger than 99% probability that you have heard an episode (or 100) of 99% Invisible. If you haven’t, I certainly envy you. Over the years Roman Mars has created an incredible audio library that explores the built world in a way you don’t expect. The show has provided huge amounts of inspiration here at Stet.Build.

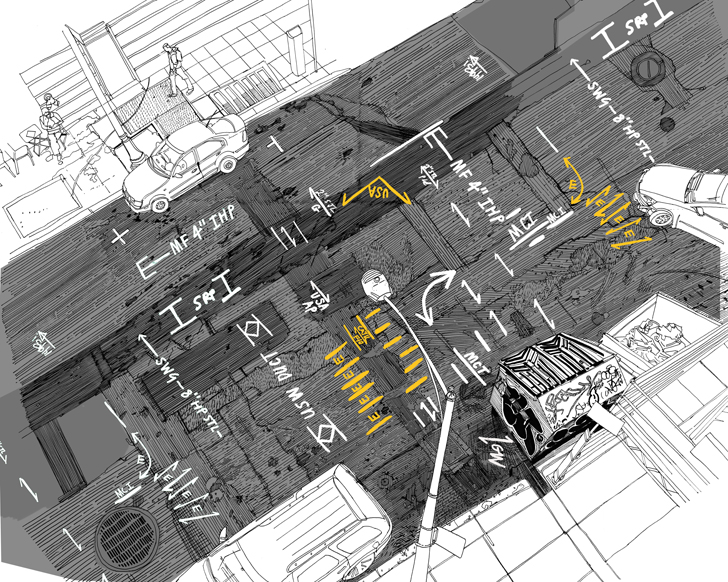

In their first foray into the publishing world, Roman Mars and producer Kurt Kohlstedt have put together The 99% Invisible City. A book that aims to captures the spirit of the show in written form. Available to buy at all good bookstores. Bonus. The incredible illustrations for the book are by Pat Vale and in this post you can watch these illustrations being made.

Tools of the Trade

Signify 3D Printed Luminaires

3D printing remains the realm of the tinkerer, the hobbyist and the early adopter. While there are a plethora of super interesting use cases for the technology it remains fringe. Signify, Philips’s renamed lighting division (from 2 years ago), is hoping to find a mass consumer use case (made from recycled plastics). Available in both professional and consumer versions, they offer a level of customization and personalization previously unavailable at any price.